( Live Encounters Poetry & Writing Volume Five November-December 2024: https://liveencounters.net/2024-anniversary-editions/percy-aaron-all-for-nothing/ )

In a tiny village in northeastern Laos, poverty and misfortune make a tragic combination.

Mouk broke the hearts of all the young men in the village when she married Tham. Her beautiful face, twinkling black eyes and large dimples always made people feel special when she smiled at them.

Tham broke the hearts of all the young girls in the village when he married Mouk. He was goodlooking, muscular and hardworking. Unlike most of the other young men, he didn’t laze around playing cards, chewing tobacco or getting drunk. If he wasn’t in the field working alongside his father, he was helping his mother inside and outside their little hut. He was especially skilful at carving little figures from the pieces of wood that he saved from the kindling. Almost every child had a whistle, or a catapult made by him.

When little Pok was born all the village rejoiced. She was such a happy baby and like her mother, there was always a smile on her face. Everybody wanted to carry or play with her. By the age of four she was totally unafraid, hunting frogs and birds with her cousins.

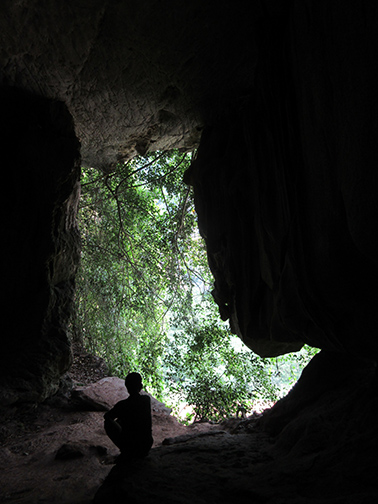

One day, she wandered into the forest with the boys but lost them. A few hours passed before some of the children told Mouk. Dropping everything, she sent one of them to call Tham from the field and rushed off in the direction the children had last seen Pok. Soon Tham and a few villagers followed with sticks and knives. The forest while a source of food for the villagers, also had its dangers. There were plants that caused terrible allergies, poisonous snakes and occasionally wild animals. Some of the villagers even claimed that they had been chased by man-eating tigers. But the greatest danger of all were the bombies, little pellets designed to maim. American warplanes had sprinkled them indiscriminately during the war next door in Vietnam. These were uppermost in the panic-stricken minds of Pok’s parents.

Then they found her but their joy turned to horror. The little girl was standing at the edge of a large puddle laughing gleefully at the ripples she was causing each time she threw a stone into the water. The horrified villagers fled as a screaming Mouk grabbed Pok by the hair and slapped her several times.

By the time Pok and her parents had returned to their hut, word had spread about the child trespassing onto sacred land. Now nobody knew what revenge the enraged forest spirits would extract for their abode being defiled.

Over the next several days, Pok was locked inside their tiny room and various rituals were performed to propitiate the spirits. Tham and Mouk borrowed heavily to pay for the ceremonies.

Months later, little Pok fell sick. She started having seizures and losing consciousness. The whispers started as villagers remembered her throwing stones into the sacred pond. The village shaman prescribed various potions for the child and even more acts of atonement but nothing helped. Clearly the spirits were upset and she was being punished for desecrating sacred land.

When the shaman’s potions had no effect, the village chief told her parents to take her to the district hospital. The inexperienced and poorly trained doctor prescribed a course of antibiotics that left Pok very weak and even more disoriented. More visits to the hospital followed and Tham and Mouk went further into debt. There were evil spirits inside the girl’s head, the parents learned. Then a kindly nurse told them to take the girl to a hospital in Vientiane, the national capital. The treatment would be very expensive but there was no guarantee that their child would get better. They were devastated.

Back in the village, Tham, Mouk and his parents discussed what should be done. They pleaded with the villagers for help but the people were poor themselves. Besides, they were afraid to incur the wrath of the spirits.

Then the headman told them about factories in Thailand, where many people from other villages had gone to work, sending home more money every few months than they could ever earn from years of working their rice plots in Laos. Tilling the fields was more a man’s job and the factories preferred women whose work in garment-making was more delicate.

* * * *

Mouk and several women from her village had already spent a year at a garment factory in northeastern Thailand. The work was backbreaking but the long hours kept her mind off her family back home. Every time a colleague went home for a holiday, she sent back whatever she had saved. Then she waited eagerly for their return and news of her family. Tham and Pok missed her terribly, she was told. Also, Tham’s father had passed away and now he worked the fields alone. She considered visiting him and Pok but thought of all the money she would lose if she took a few weeks off. Next year, she would, she kept telling herself.

One day, Mouk overheard some of the women talking about places in Bangkok where girls earned more than 25,000 baht a month. That was incredible! With that kind of money, she could return home in a few months to start Pok’s medical treatment. An older woman told her that since she was beautiful, she could earn even more. Mouk didn’t understand that remark and gave it no thought. She and some of her friends discussed the matter and agreed to move to the Thai capital.

At the end of the month Mouk and two other young women arrived in Bangkok. The brother of the woman who had told them about the job met them at Mo Chit bus station. He would take them to a place where they could easily earn more than 25,000 baht a month, he assured them. Twenty-five thousand baht a month! Their faces filled with disbelief and greed. On the way Mouk’s mouth opened in amazement. Each building they drove past had more lights than her entire village. She couldn’t believe that there were so many cars and so many people in the world.

The taxi stopped at a building and they were taken into an office. A man and an elegantly dressed woman sat at a table that was bigger than Mouk’s house back in Laos. A younger man, with bulging biceps stood at the door. The woman, who was clearly the boss, told them to take off their clothes. Mouk was shocked. Only her husband had seen her naked. She stood staring at the woman unsure she had heard correctly. There were always misunderstandings in Thailand even though Lao and Thai were almost similar. After all she did have problems even understanding Lao, which was quite different from her native Khmu.

The other women shyly removed their blouses but Mouk stood still. The woman nodded to the man at the door, who stepped forward and slapped her hard across the head. Then grabbing her shoulders, he ripped open her T-shirt and pulled off her bra. He was powerful and before she could resist further, he had already yanked off her jeans and panties. The three women stood stark naked while the woman looked up and down at their bodies.

She barked something at the man who gave them back their clothes and led them to an upper floor where they were shown a room with a couple of mattresses on the floor and some wooden lockers.

Mouk was surprised when the next morning she did not have to rise early for work. Instead, later in the morning, another woman came to the room and told them that they would start work each day at 4.00 pm and finish at 3.00 am. They were given some beautiful clothes to wear and shown how to make up. kind of work they would have to do and were told they would have to sit and talk to men, pour their drinks, and try to get them to consume as much alcohol as possible. If the men wanted anything more, they could take them to the rooms upstairs, charge more and keep half the money.

The first night the thug who had hit Mouk in the boss’s office, raped her. He told her that he wanted half of all the money she made if she took customers to the rooms. Over the next six months, Mouk lost count of the number of men she had sex with. Some were gentle and generous, but others brutalised her.

A few times she wanted to take her life, but what would happen to Pok and Tham? True, she was making a lot more money than she had ever seen and another woman showed her how to hide her money inside her body. This way, she didn’t have to share everything with the young minders who took not only half their earnings, but also expected sex for free.

A doctor would visit them regularly for checkups, stressing the importance of making the customers wear condoms. Yet, he seemed to forget to wear one, when he got his free sex. Mouk stopped heeding his advice. If the customers didn’t want to use condoms, then she charged them double. It was simple.

Slowly the people in the club became like family. One of the minders, now her regular lover, brought her little gifts. On Sunday mornings the women women visited the local markets where Mouk bought clothes, cheap trinkets and fluffy toys for Pok. She even opened a bank account secretly and had already saved over 20,000 baht. She no longer sent money home when she found out that more than half was being pocketed by the carriers.

It was almost three years since she had left her village in northeastern Laos but every time she thought of returning, she decided to wait a few months longer and take back more money.

One Sunday morning, the girls wanted to go to Chatuchak, the massive weekend market but Mouk didn’t feel like joining them. She was feeling very tired. Her last customer had been with her till almost 4.00 am. Two days later she didn’t feel better and the doctor diagnosed the flu.

When she didn’t improve after a week, two of the girls accompanied to the hospital. She had to stay for a few days so that some tests could be done. One week later, there was no improvement and a friend from the nightclub came to the hospital with a suitcase containing her things. The Peacock Bar didn’t want her back. She had some terrible disease and would have to look for work elsewhere. Mouk was too tired anyway and put off the idea of looking for another job.

A fellow patient invited Mouk to share her hovel alongside the railway tracks. Too weak to work, she lay on a plastic sheet in one corner all day long. When she could struggle out of bed Mouk started working the streets, servicing street vendors and junkies, often in darkened doorways or inside the shack, if the others were at work.

As her conditioned deteriorated she didn’t have the energy to even get out of bed, soiling the rags she slept in. Soon she was too sick to even use the bedpan next to her. As the stench of shit got too much to bear, her hovel-mates threw her out. Back in the hospital, the staff didn’t seem to care.

A nurse suggested she go back to Laos; at least she would have family to take care of her. Back to Laos, she wondered? She hadn’t even thought of her husband and daughter in months. It had been more than a year since she had even received word from them.

A week later her lifeless body was heaped upon another in the police morgue.

In Mouk’s village in Laos, Tham wondered why there was no word from her. It was almost a year since he had heard from her and even longer since she had sent any money home. How he missed her! Even four years after she had left, he had still not got used to her absence. Fortunately, he had Pok, the spitting image of her mother, to keep him company. But some nights when the young girl cried for her mother, it was difficult, very difficult, not to shed tears too.

Each evening the other men in the village would meet for a drink and endless gossip. Tham could have joined them to ease the loneliness but he preferred to play with Pok and chat with his mother.

One day when the thought of another night without Mouk got too much, Tham decided to walk to the village where one of the girls who had left with Mouk lived. Maybe, they had some news. The village was about ten kilometres away and if he cut through the forest he could still be back by midnight.

The bombie that Tham stepped on, gave him no chance.. When he didn’t return by the next morning, his mother went to the village chief for help. By the time they found him, he had bled to death.

After the death of her son Tham’s mother tried to get in touch with Mouk. Word came back that she had left the garment factory more than two years earlier to work in Bangkok. They knew nothing of her current whereabouts.

After her father’s death Pok became even more introverted. The villagers shunned her as she was bad luck. Sometimes, they urged her grandmother to abandon her in the forest.

One day a team of researchers from the Institut de la Francophonie pour la médecine tropicale visited the village to gather data. Pok’s grandmother heard that some foreign doctors were among them. The old woman went to the camp they had set up and spoke to one of the volunteers accompanying the team. The young woman turned to the tall, white man and spoke to him in a language she didn’t understand. The foreigners talked to each other and asked to see the little girl.

The old woman took them to her hut and and watched as one of the doctors stuck a strange tube into his ears and then hold the other end against Pok’s stomach then chest. He pressed her stomach again and again and asked to see her tongue. The two white men and the young Lao woman continued speaking in their strange language. After a while, the young woman told Pok’s grandmother that they wanted her to bring Pok to Vientiane for some tests. She would not have to pay for anything, they assured her.

In Vientiane other doctors performed more tests on Pok. After a series of tests, a woman in a white coat, who spoke Khmu, mentioned words like epilepsy and phenobarbital, which meant nothing to the old woman. They gave her tiny white stones and told her that Pok must swallow one every day, for the rest of her life. And that soon Pok would be a healthy young girl.

© Percy Aaron

Percy Aaron is an ESL teacher at Vientiane College in the Lao PDR and a freelance editor for a number of international organisations. He has had published a number of short stories, edited three books and was editor of Champa Holidays, the Lao Airlines in-flight magazine and Oh! – a Southeast Asia-centric travel and culture publication. As lead writer for the Lao Business Forum, he was also on the World Bank’s panel of editors. Before unleashing his ignorance on his students, he was an entrepreneur, a director with Omega and Swatch in their India operations and an architectural draughtsman. He has answers to most of the world’s problems and is the epitome of the ‘Argumentative Indian’. He can be contacted at percy.aaron@gmail.com