(A version of this article was first published in Live Encounters, August 2021: https://liveencounters.net/2021-le-mag/08-august-2021/percy-aaron-misadventures-in-the-mountains/)

From Hatsa, a small trading post on the banks of the muddy Nam Ou River in remote northern Laos, we sailed upstream through some stunning and largely unspoilt scenery. At times the colour of the water changed to a deep ochre. The current was strong and the boatman guided us skillfully past the occasional rapids splashing water onto everyone and filling up the boat. His assistant sat on the prow using an oar to push the craft away whenever it got close to any of the rocks. On placid stretches he kept himself busy baling out the water.

At regular intervals the boat stopped for villagers to get on or off and after about forty-five minutes it was our turn. We waded onto a sandy, deserted bank. All around us the high hills were covered with tall trees and dense vegetation. The only sounds were the rushing waters and the various bird calls, some recognisable, most not.

Indian file, we started climbing through dense undergrowth. At times the vegetation was so thick we could see only a few steps ahead. I pulled my cap tight over my head and covered my face with my hands or elbows to protect it from nettles and thorny twigs. Almost immediately the leeches started feasting on us, while the mosquitoes hovered around waiting their turn. We climbed and climbed and I slipped and slipped. Bringing up the rear, it was difficult to keep up with David and Souk, our guide, who had to stop frequently to allow me to catch my breath.

After about an hour of steady climbing I was totally exhausted and just couldn’t go on. I suggested they continue without me. Finding my way back would have been impossible and I was secretly relieved that David disagreed.

Soon I sat down on the path, dizzy from exhaustion and hunger. Sweat poured down my face and back as mosquitoes and large red ants bit me. David opened his backpack and gave me some biscuits and water. After a while I felt better but still didn’t think that I could make it.

David insisted on carrying my backpack and though I felt bad about it, agreed. He then had the brainwave of making me lead the group with the guide bringing up the rear. Souk handed me a thick branch to help me climb. For whatever reason, the journey was now easier with me setting the pace. We still stopped numerous times for rest breaks or to photograph the stunning scenery.

Despite the cool mountain air, we were covered with sweat and David, in particular, looked as if he had just stepped out of a sauna. After some time, we reached a clearing and took a longish break. Souk produced some juicy pears from his backpack and told us that this spot was usually the first stop on the trek – we had already stopped dozens of times – and that we were well behind schedule. Our four-hour trek, he felt, was going to be nearer six or seven hours.

We continued to climb with regular breaks for rest or photographs. As we tired, we conserved energy by keeping quiet, each of us lost in our thoughts. Except for the occasional bird call or rustle of leaves, the silence was total. For somebody like me, allergic to noise, the sensation was incredible. This was nirvana.

We ran into some colourfully-dressed ethnic women speaking a dialect that even Souk couldn’t understand. One of them stuck her hand into the bushes and pulled out a bunch of grape-like fruit and offered it to us. They were deliciously tangy.

By early evening, about six hours later – and just one hour behind schedule – we reached the top of the mountain and the Akha village of Ban Jakhampa.

Ban (or Village) Jakhampa was a collection of thatched, squalid huts made of bamboo. Only the headman’s place had wooden walls and a roof of corrugated asbestos. Built on the slopes of the mountain, they seemed ready to collapse like a pack of cards. Except for the sounds of cocks crowing and cattle lowing, the village was eerily quiet, almost like a ghost hamlet.

We walked past a number of huts towards the home of our host, the village headman. As we approached, people started popping out of their huts. They stopped what they were doing, or not doing, and stared at us with a mix of suspicion and curiosity. Some way behind, children had appeared and were following us. Much like the Pied Piper of Hamelin, their numbers were growing. Obviously outsiders, especially foreigners, were a rarity in this place.

We arrived at the village chief’s hut, took off our shoes and entered. We were told to keep them on but out of habit had left them outside. Once inside though, I saw how dirty the earthen floor was and after a while went outside and put my shoes back on.

Despite looking small from the outside, the interior was surprisingly large with a big, soot-blackened stove in one corner. None of the huts had windows, and many had low doors. We wondered why Akha building techniques did not include these, since there was no electricity. However, with the cold Phongsaly winters, having no windows probably made sense. Snot-nosed children, dogs and chickens roamed inside freely. Everybody spat anywhere and one child urinated near me. Souk, the guide was given a basin with a little water and after washing his face, threw the rest in the corner near the bed. When it was our turn we did the same.

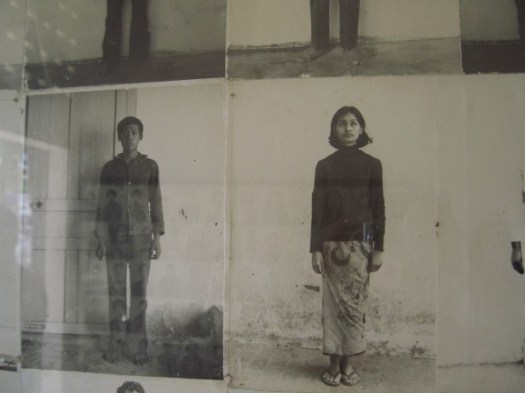

Left: Inside the village chief’s hut. Right: Sleeping quarters in the hut.

Though there was no electricity, the hut had a TV and VCR. Later, somebody explained that when rice was being milled, they ran a generator. This was the opportunity to watch a movie or two. The villagers loved Hindi films and I understood why Bollywood movies, with all their oomph and glamour, were so popular among these impoverished people.

We went outside the hut to look around and by now there was quite a large gathering waiting to catch a glimpse of us. The older boys stood close, while the younger ones watched nervously from a distance. I tried to photograph them but they fled as if they had seen a ghost.

After a while we were called into the hut for a bite. Souk had brought some food from Phongsaly. It was a very spare meal of sticky rice, strips of dried beef and some steamed vegetables, washed down with hot green tea. Later, we were offered some opium but politely declined. The village had no toilets and so after the meal we went for a walk to relieve ourselves. We were given a big stick to keep the pigs, and sometimes the dogs, at bay.

The Akha, one of Laos’ many ethnic groups, are animists. They believe that everything, living or otherwise, has spirits and must not be offended by any word or deed. To this end their whole lives are governed by ritual. An abjectly poor people who prefer living in the highlands, they practise swidden or slash-and-burn agriculture. The women in the village wore colourful headdresses, decorated with beads and silver coins; the more elaborate, the better the dowry they had received. Those carrying little babies, moved around with one breast exposed. The unmarried girls generally stayed indoors. Like many mountain people, the womenfolk seemed to do all, or most of the work, while the men just sat around smoking. The younger men too hung around aimlessly, often preening themselves, while the poorly-clad children, most of them with runny noses, seemed so listless.

Life is a very harsh and dead-end existence for these simple people.

As the sun set, David and I sat outside on a wooden platform, looking out onto the valley and chatted with our guide or those who could speak some Lao. Some asked me about their favourite Bollywood stars, but not being a movie or TV person, I must have disappointed them. Many of the younger men walked around with red – yes, all of them were red – ghetto blasters which got louder as darkness descended.

Later, Souk offered us some more food but I refused pointing out that we had just eaten. The truth was that with no toilets I wanted to eat as little as possible. An anthropologist once told me that when researching in such remote areas, he always carried a big stick to fend off pigs and dogs trying to get at his excrement before he had even finished.

As the sun went down David and I sat on the platform discussing poverty and development. Souk told us that government had plans to move the village to the base of the mountain so that education and healthcare would be more accessible, but the villagers were ambivalent about this. The younger ones thought it would bring jobs and modernity. The older villagers were sceptical of officialdom’s promises. Besides, leaving the land would cut links with the spirits of their ancestors.

Dusk made the village noisier with the many ghetto blasters at full volume. I wondered if this was to scare away the spirits. Many of the young men also carried Chinese-made torches that pierced the darkness like searchlights seeking out enemy aircraft.

Night came and despite the insomniac roosters in the village, I slept surprisingly well. The next day I stayed in bed for as long as possible to delay the need for a clean toilet.

When it was no longer polite to stay in bed I joined David outside on the observation platform. A little later Souk brought me some water for a wash. It was barely enough to brush my teeth. Later he brought us some dry bread rolls and hot coffee. Coffee never tasted better. We munched our rolls and admired the mountains, most of them covered in the early morning by a thick mist. I had never had a breakfast amidst such spectacular scenery.

We left Ban Jakhampa at 8.05 am on the return leg of our journey. As we set off, we saw it was raining on some of the distant mountains. We had been lucky with the weather until now, and were sure that our luck would hold. Souk told us that we were returning by a much shorter route and should reach the Nam Ou boat a little after noon.

Once again I led the group, followed by David and then Souk. About fifteen minutes into our journey, it started drizzling. Souk gave me a plastic poncho but it was hot and sticky and kept getting between my legs. Then the drizzle got heavier and soon we were soaked and miserable.

After about an hour, our descent started turning into a nightmare.

Coming down a mountain is more difficult than ascending and even worse in the rain. It should have been obvious that if our return route was shorter, the descent would be steeper.

Some of the paths were about a foot wide and animal hooves had worn them off making sections even more treacherous. Soon I began to dread them. On portions where the tracks were slippery, I put my foot into the grooves made by the animals to avoid sliding off the mountain.

Despite this, I moved faster than David and the guide. On one slippery stretch, when I almost slid off the path, I thought it prudent to slow down and let them keep up with me. It occurred to me that we were so insignificant in that environment, that if anything happened to us, nobody would know anything.

Sometimes the easiest looking paths were the worst. I lost count of the number of times I slipped and fell in the slush. In panic I would grab at any plant or shrub to stop myself from going over. There seemed no end in sight to this nightmare. All around us the heavy silence was punctuated by the chirruping of birds and the patter of rain on the dense foliage.

Finally, I spotted stretches of the river deep below in the distance. I calculated that it was still several hours away. Our shorter journey was turning out to be longer. After some time, I began to hear the roar of the motors from the boats far below and my spirits soared.

Two men were coming in the opposite direction and I flattened myself against the side of the mountain to let them pass on the outside. There was hardly any space between me and the edge but they went by as nimble footed as mountain goats. They said something which I did not understand.

A few minutes later I heard David and Souk shouting and stopped dead in my tracks. I called back but there was no reply. I sensed some urgency and turned back to look for them.

The men who had passed me told Souk that the Lao Theung – another ethnic group – village we were approaching was closed to all outsiders for the day. Somebody had died and as per their customs, no outsiders were allowed near the village. The thought of going all the way back filled us with horror and we pleaded with Souk to explain to the villagers that we were just passing through to catch the boat. He was adamant that we could not enter the village that day. Animists are very strong in their belief that any deviation from their rituals will anger the spirits and that it could take weeks, if not years, to placate them.

Souk turned back to look for an alternate route and we trudged behind dejectedly. After about fifty metres, he stopped, looked down and then jumped off the path. From about ten metres below he beckoned us to follow. I have a fear of heights and was in sheer panic. Once again, I begged him to reason with the villagers but to no avail. In these parts Souk was as much an outsider as we were. With my heart in my mouth I lay flat on the slushy path and started lowering myself over the side. I grabbed at every plant or shrub, thorny or otherwise. When David followed me, I saw how caked with mud he was.

We stepped into a rivulet and started following the current. The water was cold and smelled foul. I looked up to see the exposed buttocks of a villager on a ledge, defecating into the stream right on top of us. The nearest we got to the Lao Theung that day, was to their sewage.

Finally, we reached the banks of the Nam Ou River, five hours after we had set out. The relief when we saw the bank, the boats and the river was unimaginable.

© Percy Aaron

Incredible experience -surely one that will not be forgotten in life!!!

Teresa

Nice !!! and funny, I like you story, it’s very great experience !! I have never been there, I wish I’ll visit some day !!!

B^^

Jheez all that way and no fish! Mate you’ve been in the sun too long. Seriously Percy – never thought higher of you, well done brother!

David Ridler

Epic journey Percy. You are a braver man than I!!

Quite a story!! Certain parts of the story brought back memories of forgotten adventures. Very well written!!